Unilever has been through something of a PR disaster in recent weeks.

In January, Terry Smith questioned why Unilever felt that Hellmann's mayonnaise needed to have a social purpose beyond tasting great. Shortly after that, Smith wrote a somewhat scathing post-mortem of Unilever's recent attempt to buy GSK Consumer Healthcare, calling it a "near-death" experience.

So are the wheels falling off the Unilever wagon, or is this all just a storm in a teacup?

Table of Contents

- Unilever's long-term dividend growth record is still exceptional

- Unilever's recent growth has been far more pedestrian

- Unilever's return on capital employed has been going in the wrong direction

- Step 1: Double down on brands with a social purpose

- Step 2: Turn the acquisition dial up to 11

- Step 3: Simplify Unilever's management structure

- Is Unilever still a quality dividend growth stock?

- Is Unilever good value at its current price?

- Why I'm still holding Unilever

Unilever's long-term dividend growth record is still exceptional

Unilever's dividend history shows an almost unbroken record of dividend payments going all the way back to its founding in 1929. In fact, other than during the Great Depression and World War II, Unilever's dividend has gone up almost every year for the best part of a century.

Equally impressive is the fact that between 1979 and 2017, its dividend grew at an annualised rate of 8%. But trees don't grow to the moon and no company can outgrow the rest of the global economy forever.

Unilever's recent growth has been far more pedestrian

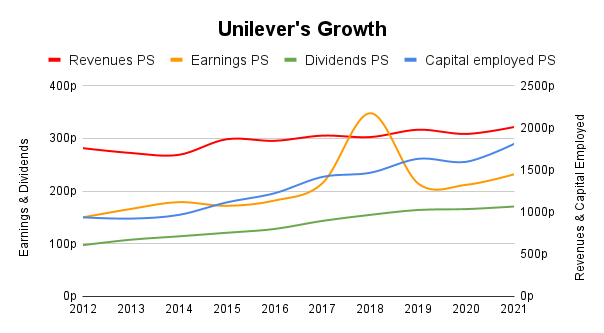

If we look at just the last ten years, Unilever's track record begins to look a lot less impressive.

Here are a few stats:

- Capital employed has grown by around 9% per year since 2012

- Revenues per share grew by around 2% per year

- Earnings per share grew by around 4% per year and

- Dividends per share grew by around 7% per year

At first glance, that doesn't look too bad. After all, the dividend still went up by 7% per year, which is impressive for such a large and mature business.

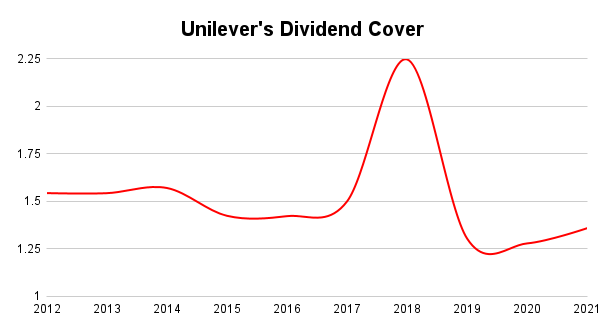

But there's a problem. Dividends are paid out of earnings and Unilever's earnings have only grown by 4% per year. If dividends consistently grow faster than earnings then dividend cover falls, and that means a less secure dividend and fewer earnings to reinvest within the business to drive future growth.

And that's exactly what we see, with Unilever's dividend cover falling from 1.6 in the early 2010s to 1.4 today. That doesn't sound like much, but it represents a 33% decline in the proportion of earnings being reinvested to drive growth.

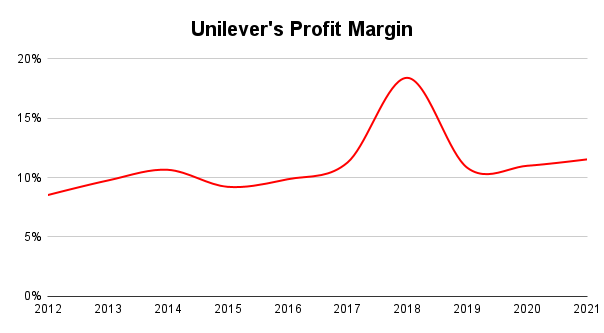

But it gets worse. Unilever's earnings per share have grown by 4% on average, but its revenues per share have only grown by 2% per year. This is a problem because earnings can only grow faster than earnings if profit margins are widening, but profit margins cannot grow forever. At some point, they're as fat as they're ever going to be and at that point, earnings cannot outgrow revenues.

In Unilever's case, profit margins have increased from about 9.5% a decade ago to 11% today.

If profit margins can't be pushed much higher, Unilever may have to settle for very low single-digit EPS growth in future.

However, a more positive viewpoint (which I tend to agree with) is that Unilever has spent much of the last decade tilting its portfolio of brands towards higher-margin areas such as beauty and healthcare, and away from lower-margin areas such as margarine and other spreads.

This shift has inevitably led to a reduction in revenue growth as low-margin brands (i.e. those with high revenues but low profits) have been sold off.

Once this transition is complete, margins should stabilise and revenue growth should increase, assuming management does a halfway decent job of running the business.

Unilever's return on capital employed has been going in the wrong direction

Unlike revenues and earnings, Unilever's capital employed (property, machinery, inventory and other assets funded by shareholders, lenders and landlords) has continued to grow rapidly, at an average rate of 9% per year.

That's good in one sense because Unilever has clearly been investing for growth, by acquiring other businesses and investing in the technology necessary to improve its products. But the fact that capital employed has grown faster than earnings is not good news, because it means that Unilever's return on capital employed has been falling for years.

The chart above shows that Unilever's return on capital employed has reduced from around 17.5% in the early 2010s to 13% or so today. That's a fairly substantial decline and it may have occurred for one or more of several reasons:

- Unilever has become less competitive and its pricing power has been eroded by its peers

- Unilever has grown its capital base unwisely by investing in low-return acquisitions

- Unilever has just gone through a temporary period of underperformance due to random internal and external factors

I think all three of those statements are true to some extent.

Losing competitiveness: Unilever has been less competitive in recent years, but that shouldn't be a surprise. Capitalism is a brutal fight to the death for most companies, so investors should expect companies to occasionally be outclassed by their peers.

Unwise acquisitions: This has certainly been true in some cases, notably Dollar Shave Club. But management has said that most of its acquisitions in recent years have produced more than acceptable returns, and I have no reason to think they are lying.

More generally, it can take years for acquired businesses to become fully integrated and to take full advantage of Unilever's product development and distribution capabilities, so a degree of patience is required.

Temporary factors: Even if a company does everything right, you should still expect things to occasionally go wrong, simply because the world is a volatile and uncertain place. So the fact that Unilever has had a difficult few years isn't in and of itself a reason to panic.

Of course, just because these headwinds have reasonable explanations, that doesn't mean shareholders have to lie down and accept Unilever's weak performance.

Many shareholders have been voicing their concerns for years and in response, management has been taking increasingly bold steps to improve Unilever's growth. However, some of these steps have upset shareholders even more than Unilever's slow growth rate.

Step 1: Double down on brands with a social purpose

Unilever has been focused on social purpose from the very beginning, with its co-predecessor Lever Brothers taking a Quaker-like multi-stakeholder approach to business, even going as far as building a village (Port Sunlight) for its Sunlight Soap factory workers.

So it should come as no surprise that today, Unilever aims to be a sustainable business creating value for all stakeholders (including shareholders) through its purpose, which is to make sustainable living commonplace.

To achieve that overall purpose, management has said that every Unilever brand should be a brand with a clear social purpose. For example:

- Dove's purpose is to make a positive experience of beauty accessible to all women

- Ben & Jerry's purpose includes advancing human rights, supporting social justice for marginalized communities and protecting the Earth's natural systems

- Domestos's purpose is to win the global war against unsafe sanitation and poor hygiene

The purpose of Hellmann's mayonnaise is to help people enjoy good, honest food, for the simple pleasure it is. That sounds sensible enough, but Hellmann's has another purpose, which is to help reduce the vast amount of food wasted every year. It aims to do this by encouraging people to turn leftovers into another meal with the help of a little Hellmann's mayonnaise, rather than throwing those leftovers in the bin.

Giving Hellmann's a purpose beyond making food taste great seems to have been the straw that broke the camel's back, at least for Terry Smith, who said:

"A company which feels it has to define the purpose of Hellmann’s mayonnaise has in our view clearly lost the plot."

That seems self-evidently true. But is it? After all, various studies have shown that on average:

- Baby Boomers (aged 60-80) are not interested in a brand's social purpose.

- Generation X (aged 40-60) say they like brands with a social purpose, but in practice, they tend to buy based on price and quality with little regard for social purpose.

- Gen Y (aged 20-40) buy products and services because of the brand's social purpose, but only if price and quality are not overly negatively impacted.

- Gen Z (aged 0-20) favour brands with a positive social purpose even at the expense of price or quality.

So there is a clear trend, from generation to generation, of brands' social purpose becoming more important to consumers.

There is also evidence that Unilever's purposeful brands grow faster, and there's evidence that brands with a social purpose beyond profit grow faster across a wide range of industries.

So giving Hellmann's mayonnaise a social purpose beyond profit is not a sign that management has lost the plot. It is a sign that Unilever is, somewhat counterintuitively, attempting to maximise long-term returns for shareholders by focusing on what the consumers of the future (Gen Y and Z) actually want.

For more on the confounding logic of maximising profits or perhaps even happiness by not seeking them directly, see John Kay's book, Obliquity.

Step 2: Turn the acquisition dial up to 11

One of the best ways to drive rapid growth is to buy it. In other words, to acquire other businesses rather than build up similar operations from scratch.

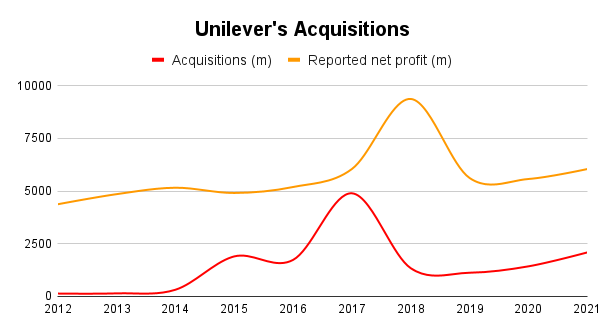

Unilever has a long history of evolving its brand portfolio through acquisitions and disposals, and over the last decade, the company spent around €15 billion on acquisitions.

That's a lot, but Unilever earned almost €60 billion over those same ten years, so its acquisitions only came to about 25% of its profits, which is relatively prudent.

Despite spending all those billions, Unilever's recent growth still isn't impressive, so management decided to turn the acquisition dial up to 11 by offering to buy GSK Consumer Healthcare for £50 billion.

£50 billion is about equal to all of Unilever's profits over the last ten years and it's about half of Unilever's current market cap. So by any reasonable definition, this would have been a huge acquisition.

Of course, management thought this acquisition was a good idea. It would take Unilever into new markets, like over-the-counter (OTC) health products, and Unilever's very large footprint in emerging markets could speed up the acquired business's growth in those regions.

But the deal never happened because institutional shareholders were, in general, horrified by the idea. As I've already mentioned, Terry Smith wrote a strongly-worded post-mortem outlining his grievances.

Some of the key problems with the deal were:

Debt: The acquisition would be funded largely with debt and since Unilever already has more debt than I'd like, this would have left the company very heavily indebted.

Disruption: Fully integrating a £50 billion acquisition is no easy task, and very large acquisitions have a history of taking focus away from the acquirer's core business.

Price: The £50 billion price tag seemed high, given that GSK Consumer Healthcare only has revenues of £10 billion and earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) of around £2.5 billion. So at that purchase price, the EBIT yield is just 5% and the potential "dividend yield" (i.e. cash that could be returned to the core Unilever business) would probably be around half of that, i.e. 2.5%.

Personally, I'm glad the deal didn't go ahead because I'm not a fan of big acquisitions and the debt and disruption they often bring. But that doesn't mean the deal was a bad idea. The truth is we'll never know if it was a good idea or not because it didn't happen.

Step 3: Simplify Unilever's management structure

Unilever is a large and complex business selling lots of different products at different price points and through different distribution channels. To cope with this complexity, Unilever evolved its organisational structure into a matrix, where employees report to multiple managers.

This matrix structure has served Unilever well for decades, but now it's seen as being overly complex, slow to adapt to a changing competitive landscape and expensive to operate, with too many layers of management. So Unilever is switching to a simpler model which it hopes will be more adaptable, higher performing and cheaper to run.

The plan is to separate Unilever's operations into five business groups: Beauty & Wellbeing, Personal Care, Home Care, Nutrition, and Ice Cream.

These businesses should be laser-focused on their respective product categories across the globe, operating with relative autonomy while taking advantage of Unilever's scale by sharing common infrastructure and services across the group.

Whether this will turn out to be a good idea is impossible to know, but it does show that management is serious about driving growth higher, even in the absence of the GSK deal.

Is Unilever still a quality dividend growth stock?

Despite all the gnashing of teeth from institutional shareholders over recent weeks, I still like Unilever.

It still owns many globally leading brands, it still has a very large footprint in high-growth emerging markets and it still has the scale and experience to compete against the best in the world.

Its growth rate may not set the world alight, but as a steady dividend stock, I think Unilever is still a solid choice.

Is Unilever good value at its current price?

Unilever's share price today is £38.50. Unilever's dividend is set in Euros and last year its dividend was €1.71. In GBP the dividend came to £1.46, giving a dividend yield of 3.8%. That's significantly better than you'll get from a FTSE All-Share tracker, where the yield is currently about 3.1%.

So in terms of raw yield, Unilever is better than the UK index. But what about dividend growth?

To estimate Unilever's dividend growth rate you have to make assumptions about the future. These assumptions will invariably be wrong, so to err on the side of caution your assumptions about the future should be both conservative and realistic.

These assumptions will need to answer questions like:

- How much room for growth is there in the company's core markets?

- Will it be able to expand into closely related adjacent markets?

- How much cash will the company be able to reinvest to fund its expansion?

- How much will be left over to pay dividends?

- What sort of return will the company get on its reinvested earnings?

Here are the assumptions I've used to estimate Unilever's potential for future dividend growth:

- Core market growth: Unilever sells soap, ice cream and other products that people are likely to keep buying forever, so these markets should grow roughly in line with the global economy, which has grown by around 3% per year over the last 50 years

- High-growth markets: Unilever has a significant footprint in emerging markets as well with 40% of revenues coming from the higher-growth markets of India, China and the US. Underlying sales growth in India and China has been in the high single-digits for at least the last five years. On that basis, I assume that Unilever has the potential to grow by mid-single-digits for many years.

- Return on capital: Although Unilever's net ROCE has declined in recent years, I think it's reasonable to assume that it stabilises close to its current level, perhaps at 14%.

- Dividend cover: With a 14% net return on capital, Unilever would be able to fund my assumed growth rate of 4% by reinvesting just 30% of its annual earnings. The remainder could be paid out as a dividend, which would give a dividend cover of 1.4.

- Long-term growth: Given the conservative nature of an assumed 4% growth rate, I assume that this growth rate can be maintained "forever".

The above assumptions, combined with Unilever's 2021 capital employed of €47 billion (€18.12 per share), give the following result:

- A 2022 dividend of €1.81 (£1.51), giving a forward dividend yield of 4%.

- Dividend growth of 4% essentially "forever"

- An expected annualised total return (on a yield-plus-growth basis) of 8%

Those estimated returns are all above the market average, so it seems to me that Unilever is somewhat attractively valued at its current price.

We can go a step further and estimate Unilever's "fair value", i.e. the price at which Unilever would be expected to produce returns in line with the long-term UK market average of 7% per year.

Using my investment spreadsheet, it's easy to calculate the present fair value of those estimated future dividends, and based on the assumptions above, my estimate for Unilever's fair value is £47.83.

With a share price of £38.50, Unilever is trading below that estimated fair value with an estimated upside is 24%. In other words, if the price increased to my estimate of fair value tomorrow, we'd see a capital gain of 24%.

That isn't bad, but it isn't fantastic either and quite a few of the holdings in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio have estimated upsides of more than 100%.

We can also work out the share price we'd need to see for Unilever to produce a total return of 10% annualised, which is a fairly common target for income investors.

Using my spreadsheet again, and based on the previous assumptions, my estimate for Unilever's "good value" price comes out as £23.80.

Here's a quick recap of those numbers:

- My "fair value" estimate (7% expected annualised return) for Unilever is £47.83

- My "good value" estimate (10% expected annualised return) is £23.80

- The current share price is £38.50

Why I'm still holding Unilever

Unilever has been in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio since late 2020 and I have no intention of selling it just yet.

I still think it's a high-quality company and I still expect it to produce steady dividend growth for many years.

Whether that growth ends up being in the mid or high single-digits is unknown, but based on a set of conservative assumptions I think Unilever is reasonably attractive at its current price.

However, it isn't super-attractively priced, at least by my standards, so although I'm happy to hold Unilever, its target position size is relatively small.

For me, with a target of holding around 20-25 stocks, "relatively small" means a target position size of 3.6% compared to my most attractive holding which has a target position size of 7%.

Hopefully, all the hullabaloo of recent weeks will stir management into action and Unilever will produce even better returns than I expect. But if not, I'm still happy to hold it at the current share price.

The UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter

Helping UK investors build high-yield portfolios of quality dividend stocks since 2011:

- ✔ Follow along with the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ Read detailed reviews of buy and sell decisions

- ✔ Quarterly, interim and annual updates for all holdings

- ✔ Quality Dividend Watchlist and Stock Screen

Subscribe now and start your 30-DAY FREE TRIAL

UK Dividend Stocks Blog & FREE Checklist

Get future blog posts in (at most) one email per week and download a FREE dividend investing checklist:

- ✔ Detailed reviews of UK dividend stocks

- ✔ Updates on the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ UK stock market valuations

- ✔ Dividend investing strategy tips and more

- ✔ FREE 20+ page Company Review Checklist

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.