Prudential plc is a FTSE 100 life insurer, offering a range of life and health insurance products to the rapidly growing middle classes of Asia and Africa.

When I added Prudential to the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio back in 2017, its earnings and dividends had grown by more than 10% per year over the previous ten years. But despite that impressive record, Prudential’s share price hasn’t performed well, and I have decided to sell the shares with a loss (offset to some extent by dividends) of 24.8% or 7.6% per year.

Unfortunately, occasional losses are inevitable when you’re investing in individual companies, so when they do occur, it is essential that we learn the relevant lessons and embed them into our investment processes so that we don’t make the same mistakes twice.

In this case, there are two lessons that income-focused investors can learn:

- Don’t invest in companies with multiple unrelated businesses

- Don’t make optimistic assumptions about a company's future growth rate

Last but not least, there is a possibility that I'm making a mistake by selling the shares at a loss, so I'll address that as well.

You can also download PDF versions of my original purchase and sale reviews, extracted from the UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter:

- Prudential Purchase Review: December 2017

- Prudential Sale Review: September 2023

Table of contents

- Lesson 1: Don't buy companies with unfocused core businesses

- Lesson 2: Don't make optimistic assumptions about long-term growth

- Pros and cons of selling Prudential versus holding

- Selling Prudential to reinvest the proceeds into high-yield stocks

Lesson 1: Don't buy companies with unfocused core businesses

Related: How to find quality dividend stocks with enduring core businesses

I like to invest in high-quality companies, and high-quality companies are usually highly focused businesses.

The good news is that in its current form, Prudential plc is a highly focused life insurer that offers life and health insurance and asset and wealth management to the rapidly growing middle classes of Asia and Africa.

Insurance and asset management may seem like very different businesses that could dilute Prudential’s focus, but the finance-related skills are similar, so it often makes sense for insurers to manage and invest their premiums themselves rather than hiring an outside asset management firm.

The bad news is that when Prudential joined the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio in 2017, it was split fairly evenly between three different businesses that were only related at a superficial level.

Those three businesses were:

M&G Prudential: In 2017, M&G Prudential had just been created by merging two of the group's divisions, Prudential UK and M&G.

Prudential UK was the original Prudential life insurance and annuities business. It was founded in the UK in 1848 and was the company behind the phrase “Man from the Pru”.

M&G was an almost 100-year-old UK-based asset management business that Prudential had acquired in 1999.

Jackson National Life: Jackson sold annuities in the US market, where it’s based. Prudential acquired Jackson in 1986 during a long and somewhat undisciplined acquisition frenzy (at one point, for example, Prudential acquired its way to market leadership among UK estate agents shortly before the UK property market collapsed in the early 1990s).

Prudential Corporation Asia: This is the Asia and Africa-focused business that remains today, and it was set up in 1994 to organise the company's existing operations in Asia.

These three businesses were all focused on the life, pensions and long-term savings markets, but there was no meaningful overlap between savings and investments in the UK, annuities in the US and life and health insurance in Asia and Africa.

When a company has multiple businesses, the whole should be greater than the sum of its parts. In other words, the outcome should be something like 1 + 1 + 1 = 5.

In Prudential’s case, given the lack of synergies between its three businesses and the additional complexity that comes with managing three separate businesses, the outcome was more like 1 + 1 + 1 = 2.

Back in 2017, I was more relaxed about focus. As long as a company’s various divisions operated within the same industry (e.g. financial services), that was focused enough for me.

What I didn’t realise was that a more aggressive CEO might turn up, decide that the company wasn’t focused enough and split the thing up. But that is exactly what happened when Mike Wells was promoted from CEO of Jackson to CEO of Prudential plc in 2016.

His first step was to merge the European businesses to form M&G Prudential, and this occurred just before I invested. That business was then fully demerged in 2019 and is now a separately listed FTSE 100 company called M&G.

His next step was to separate Prudential’s US and Asia businesses. This occurred in late 2021 when Jackson National was demerged and became a US-listed stock.

The portfolio was allocated shares in M&G and Jackson, but I didn't want to hold either, so when the dust settled, the portfolio was left with Prudential’s Asia-focused business, which is definitely more of a growth stock than a dividend stock.

The lesson here is simple:

Companies with a variety of relatively unrelated businesses, where none makes up a significant majority of the overall company, come with additional risks. They’re complicated to run, time-consuming to analyse, and they’re at risk of being broken up, with all of the uncertainty that brings.

I now strictly apply the following rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it has a focused core business generating more than two-thirds of all revenue and/or profit

Lesson 2: Don't make optimistic assumptions about long-term growth

When Prudential joined the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio, it had a share price of £18.07 and a fairly paltry dividend yield of 2.3%.

Today, I would baulk at the idea of buying shares with such a low yield, but back in 2017, I was willing to invest in lower-yield stocks where returns are expected to be driven mostly by growth rather than income.

Here’s what I wrote in my original purchase review:

“Prudential is a growth stock which appears to be available at a reasonable price. The risk here is that Prudential fails to grow faster than the market, in which case we’re left with a slow-growth, low-yield stock."

The problem was that with a 2.3% dividend yield, Prudential's dividend would have to keep growing at a high-single-digit rate, essentially forever, for the investment to make sense from a valuation point of view.

In the end, the dividend didn’t keep going up because the company split into three, so my purchase price didn’t make sense.

I then compounded this error by topping Prudential up in 2021, again on the assumption that it could continue to produce high rates of growth for a very long time.

The lesson I took from this is as follows:

Focus on stocks where returns are mostly in the form of high dividends today rather than the promise of high growth into the dim and distant future.

To avoid repeating this error, I now use the following rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Never assume that a company can grow faster than 5% beyond the next ten years

For example, I currently assume that Prudential can grow by about 9% per year over the next ten years, which is still a fairly punchy assumption. However, beyond that, my assumption is that Prudential's growth will top out at 5% per year and not a fraction more.

Pros and cons of selling Prudential versus holding

I realise that selling Prudential now could be the wrong move, so let’s have a look at the pros and cons of Prudential in order to understand what I like, what I don't like and why I'm selling.

Pro: Past growth has been consistently strong

Related: How to identify stocks with high-quality dividend growth

Having offloaded its US and UK businesses, Prudential now operates in the high-growth markets of Asia and Africa, and the high-growth nature of those markets definitely shows up in its financial results.

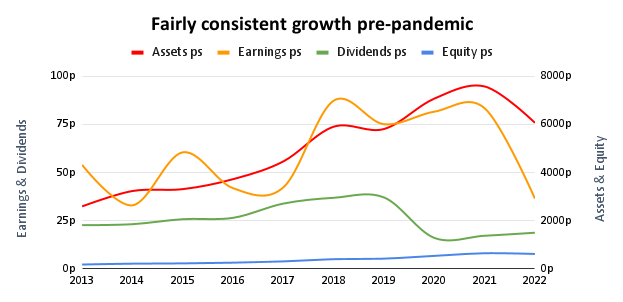

Here’s a chart showing the company’s results over the last ten years, with the US and UK businesses stripped out.

Data source: SharePad

Before the pandemic, Prudential’s assets, equity and earnings were growing fairly consistently at mid-teen rates. The dividend was cut before the pandemic, but that isn't a major problem because it was cut so that more earnings could be reinvested to fuel higher expected growth rates.

The pandemic has, of course, been a major headwind these last three years, but Asia and Prudential are on the road to recovery, and I expect Prudential to return to near-double-digit growth in the relatively near future.

Pro: Future growth is likely to be strong

One of the main arguments for investing in Prudential is that it operates in Asia and Africa, where demand for insurance and asset management services is expected to grow rapidly for many years and perhaps many decades to come.

For example, over the next ten years, these regions are expected to grow around twice as fast as the rest of the world.

This growth is expected to be driven by a rapid increase in the number of working-age middle-class people who can afford the protection and savings products that Prudential provides.

To a not-inconsiderable degree, this may offset Prudential’s lack of competitive advantages. That’s because a rising tide lifts all boats, and even mediocre businesses can thrive when demand grows faster than supply.

But there are downsides as well. These high-growth markets are also less mature in terms of regulatory development, and there is a greater risk of disruptive regulatory change, especially in China. This isn’t why I’m selling, but it is something to be aware of.

Con: Profitability is inconsistent

Related: Find quality dividend stocks using these profitability ratios

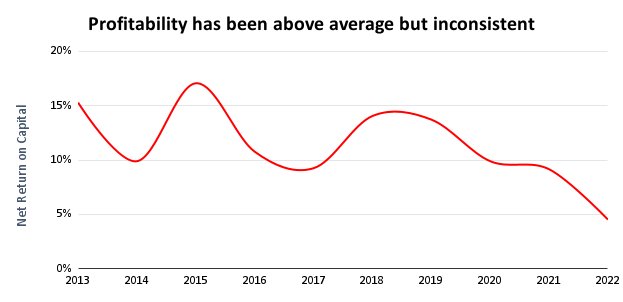

My go-to metric for profitability is net return on capital, which is the ratio of post-tax profit to total capital (the sum of equity and debt).

In Prudential’s case, its Asia and Africa-focused business has sometimes produced net returns on capital above 10%, which is quite good.

Data source: SharePad

This gives Prudential an average net return on capital of 11%, which is above my minimum threshold of 10%.

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its average net return on capital is above 10%

However, one wrinkle in this initially rosy picture is that Prudential’s net returns on capital have fallen below the 10% level in five of the last ten years. This is a sign that Prudential might not have any competitive advantages, as durable competitive advantages almost always lead to consistently strong returns on capital.

To avoid companies with weak competitive advantages and inconsistent profitability, I've recently introduced another rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its net return on capital is above 10% at least 70% of the time

Prudential fails this test, but to be fair, three of its sub-par years came during the pandemic, so this may not be an issue, but it does tie in with my next point.

Con: Competitive advantages are weak

I’m a long-term investor, so there’s a good chance that when I buy shares, I could be holding them for a decade or more. Obviously I want my investments to do well, and for companies to prosper over that sort of timespan, they usually need to have durable competitive advantages.

There are many different types of competitive advantage, but I focus on six that I’m reasonably familiar with.

(1) Market Dominance

Market dominance can provide economies of scale, brand strength, more firepower to invest in people and technology and a raft of other advantages.

My definition of market dominance is when the leader is at least twice as large as its nearest competitor, and while Prudential has top-three positions in most of its markets, that isn’t market dominance.

(2) Loved Brands

A loved brand is one where the customer chooses the brand first and then makes a purchase from that brand that fits their budget.

A typical example would be someone first deciding they want to drink IRN-BRU and then (if at all) thinking about how much IRN-BRU they can buy within their budget. This gives the owner of a loved brand significant pricing power.

Prudential’s brand is well-known in its core markets, but there aren’t many people who first think, “I want to buy Prudential life insurance”, and only then think about price.

The inconvenient truth is that few people are willing to pay more to buy insurance from a particular brand, so Prudential's well-known brand is helpful, but it isn't a durable competitive advantage.

(3) Unique Business Model

Some companies benefit from having a unique business model that gives them a lower cost base or some other advantage. But that isn’t the case with Prudential, as it has a fairly standard business model based on the synergies between life insurance and asset management.

(4) Long-Term Leadership

Some companies gain a durable advantage from consistently having leaders who are focused on ensuring the company's success over the next quarter century rather than the next quarter.

To help me spot these companies, I use Jim Collins' Good to Great model (the more concepts a company applies from that model, the more likely it is to have a long-term leadership culture).

A long-term leadership culture can be hard to spot, but it most obviously shows up as homegrown CEOs who, ideally, remain in the CEO hot seat for more than the usual five-year term.

Looking at Prudential's last three CEOs:

- The current CEO joined Prudential from a competitor in 2023

- The previous CEO joined when Jackson was acquired in 1995, became CEO in 2015 and left on good terms after seven years

- The CEO before that joined as CFO in 2007 as an outsider and became CEO in 2009

Out of the last three CEOs, only one was an internally hired long-time employee, and this suggests that Prudential's leadership culture doesn't have an unusually long-term focus.

(5) Network Effects

Network effects commonly occur in businesses that bring together two sides of a marketplace, such as eBay or Rightmove. This can be a powerful competitive advantage for the market leader, but network effects don’t generally exist in the insurance industry.

(6) Switching Costs

Some companies benefit by (intentionally or not) making it hard for customers to switch to one of their competitors.

With life and health insurance, switching to a new supplier means filling out forms and other minor hassles, so the barriers to exit aren't huge. However, the benefits of switching from one insurer to another are often so low that even relatively minor switching costs can be enough to stop customers from leaving.

Like many financial services companies, I think Prudential probably does benefit to some extent from switching costs, and as a result, many of its customers renew their insurance policies year after year after year.

This is good, but it also isn't. That's because switching costs are my least favourite competitive advantage.

In my opinion, switching costs are a supplementary advantage that can support and enhance other competitive advantages, but on their own, they are weak and potentially corrosive.

They're potentially corrosive because switching costs reduce the need to produce excellent products and services, and producing mediocre products and services is not a hallmark of a high-quality business.

Microsoft used to be famous for its overreliance on switching costs, which allowed it to produce crummy software that everyone had to use because everyone else was using it. Eventually, when serious alternatives did begin to arrive from Apple, Google and others, pretty much everyone who was fed up with Microsoft's sub-par software was more than happy to jump ship.

The conclusion to this minor detour into the world of competitive advantages is that Prudential only appears to benefit from switching costs, which isn't enough to make it a high-quality business.

Con: The share price and dividend yield are unattractive

Before we move onto the topic of price and value, here's a summary of my thoughts on Prudential as a business.

There is little doubt that Prudential is a reasonably good company, with a well-known brand and a top-three position in most of its markets. It has a 100-year history and seems to be well-run, producing double-digit returns on capital somewhat consistently and double-digit growth slightly more consistently, mostly because it operates in high-growth markets.

However, Prudential's returns on capital aren’t great, it doesn’t have any attractive competitive advantages, and it operates in markets that are both high-growth and relatively immature, which are risks as well as opportunities.

On balance, if I didn’t already own Prudential, I wouldn’t buy it because it doesn’t clearly exceed my criteria for quality, which are materially stricter than they were in 2017.

Even so, selling Prudential now could be a mistake if the price is ridiculously low, so let's take a look at Prudential's share price and valuation.

I value companies by estimating their future dividends and then calculating the present value of those future dividends by discounting them by my target rate of return (this is known as a discounted dividend model). This allows me to estimate a company's intrinsic value or fair value per share and compare that estimate to the current share price.

My preferred approach to estimating future dividends is to treat a company like a savings account.

- If a savings account contains £100 and pays 10% interest, it will pay out £10 in year one

- If I reinvest half of that (£5) back into the account, it will contain £105 and pay interest of £10.50 in year two

- If I keep reinvesting half the interest each year, the money in the account, the annual interest, the amount reinvested and the amount withdrawn will all keep growing by 5% every year

We can apply a similar model to companies by estimating their capital (the amount in the “savings account”), their net return on capital (the “interest rate”) and their dividend cover (the amount paid out vs. the amount reinvested) over the next ten years.

My default approach is to assume that a company will (a) continue to earn historically average net returns on capital and (b) maintain a historically average level of dividend cover.

Sometimes the default model needs to be tweaked to take account of the real world, but in this case, my model for Prudential is relatively simple.

My assumptions are that Prudential:

- continues to earn a net return on capital of 12% (in line with the pre-pandemic average)

- retains the majority of its earnings to fuel growth, leaving it with a dividend cover of 4.5

Here’s the full model based on those assumptions (I’ll explain the Margin of Safety and other elements of the table below).

The table shows Prudential’s dividend increasing from today's 18.8 cents to 21 cents in 2023 and then growing at 9.3% per year to 44 cents in 2031.

I think a 9% estimated growth rate is both conservative and realistic because it’s based on historical norms, and Prudential’s end markets are more than capable of supporting that level of growth.

The "2032+" column shows my estimate of Prudential’s long-term growth for 2032 and beyond. This is set at 5% per year, which is the maximum long-term growth rate I’ll assign to any company.

The bottom row of the table shows my target rate of return of 10% per year and the market average average return of 7%. Those values are used to calculate my fair value and good value estimates.

Fair value is the share price that would give a buy-and-hold investor a 7% annualised long-term return, assuming the model is 100% correct (which, of course, it won't be). This is effectively my target sell price because I want to do better than the market average.

Good value is the share price that would give a buy-and-hold investor a 10% annualised long-term return. This is effectively my target purchase price because 10% is my target rate of return.

To put it more bluntly:

- My target buy price for Prudential is £4.43

- My target sell price for Prudential is £11.35

At the beginning of September, Prudential’s share price was £9.66, so it was fairly close to my fair value estimate. This is reflected in the margin of safety score of 24%, which shrinks towards zero as the share price moves towards fair value.

At 24%, Prudential’s margin of safety falls into my sell zone, where the margin of safety is between zero and 25%. With the margin of safety that thin, it begins to make sense to sell up in order to reinvest the proceeds into something more attractive and with a wider margin of safety.

In addition, Prudential’s dividend yield was a miserly 1.5%, and that's far from ideal in what is fundamentally a high-yield portfolio.

Given Prudential's lack of quality, lack of margin of safety and lack of attractive dividend yield, the decision to sell was relatively straightforward.

Selling Prudential to reinvest the proceeds into high-yield stocks

And so, a few days ago, I removed Prudential from the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio at £9.38 per share, locking in a loss of -24.8%, or -7.6% annualised, including dividends.

That isn’t great, but sensible diversification across 20 to 30 holdings means that Prudential’s loss comes to just 1.6% of the overall portfolio, so although any loss is unwanted, this is far from a catastrophe.

And while it can be emotionally difficult to sell shares at a loss, the rational thing to do is make decisions based on our analysis of the available information. In this case, my analysis leads me to believe that selling Prudential and taking the loss on the chin is the rational thing to do, so that is what I’ve done.

I haven’t reinvested the proceeds yet, but there are a couple of attractive high-yield stocks near the top of my Watch List, and there is a good chance that one of them will enter the portfolio next month.

As a reminder, here are the main lessons again:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it has a focused core business generating more than two-thirds of all revenue and/or profit

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company with durable competitive advantages (market dominance, loved brands, unique business model, great culture, network effects, switching costs)

- Rule of thumb: Never assume that a company can grow faster than 5% beyond the next ten years

The UK Dividend Stocks Newsletter

Helping UK investors build high-yield portfolios of quality dividend stocks since 2011:

- ✔ Follow along with the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ Read detailed reviews of buy and sell decisions

- ✔ Quarterly, interim and annual updates for all holdings

- ✔ Quality Dividend Watchlist and Stock Screen

Subscribe now and start your 30-DAY FREE TRIAL

UK Dividend Stocks Blog & FREE Checklist

Get future blog posts in (at most) one email per week and download a FREE dividend investing checklist:

- ✔ Detailed reviews of UK dividend stocks

- ✔ Updates on the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio

- ✔ UK stock market valuations

- ✔ Dividend investing strategy tips and more

- ✔ FREE 20+ page Company Review Checklist

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.